By Charles E. Reineke

For the past 15 years, David Buri, a former representative in the Washington legislature, has served as Eastern’s point person in Olympia. His job title is executive director of government relations, a role his office’s website describes as “identifying, coordinating and advancing the university’s interests to elected officials.”

To put it in simpler terms, Buri is an old-school influencer. A voluble, outgoing guy in a tastefully appointed suit and Eagle red tie. The guy who shows up in Olympia and patiently explains to lawmakers, over and over, why Eastern matters. Why it matters to its students, thirty-five percent of whom are first-generation college enrollees who will, overwhelmingly, use their degrees to land well-paying jobs. Why it matters to the state of Washington, which directly benefits from the experience and expertise of the more than 84,000 EWU graduates who currently reside in the state. And why it matters to the entire Inland Northwest, which for decades has relied on Eagle alumni to power its regional economy.

When EWU’s interests are on the line, its Buri’s job to use his experience and influence to move things along. Sometimes this means personal interactions with lawmakers. But just as often it involves helping others make their cases. He smooths the path to conversations, helps prep administrators for public hearings and drafts talking points around legislative priorities. These activities and appearances often involve Eastern’s president, the obvious public face of the institution. But steering lawmakers toward other voices — faculty, staff, students and friends of the institution — is also vital.

Just under a decade ago, for example, when EWU sought state funding for its new Interdisciplinary Science Center — along with millions more for the first phase of its long-overdue renovation of its Science Building — Buri worked to ensure that College of STEM dean David Bowman was front and center in helping state politicians understand the potentially transformative nature of their investment. Mary Cullinan, then Eastern’s president, was enlisted to make a similar case, while other senior administrators, faculty researchers and standout students sold the value proposition. The full-court press paid off, and the finished ISC building, dedicated just over a year ago, is now Eastern’s most prominent calling card to a new generation of our region’s brightest science, technology, engineering and mathematics students.

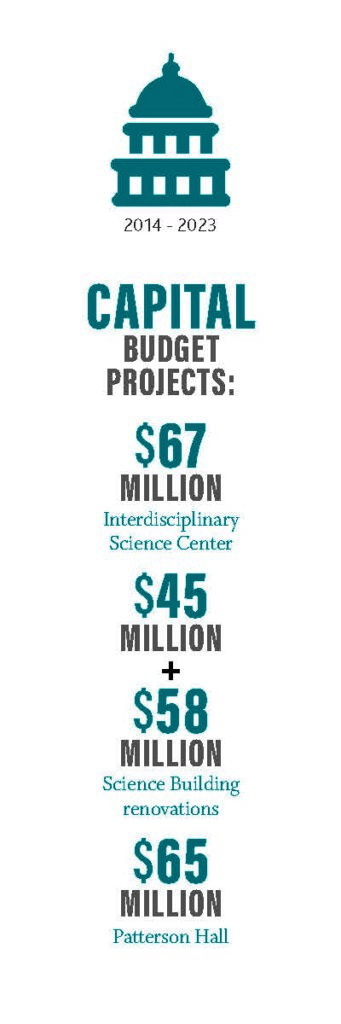

Still, as straightforward as Eastern’s case for support might seem, it’s not always an easy sell. State revenue goes up and goes down. Priorities shift even as needs change. Competing interests stake their own claims for funding. Advocating for Eastern, Buri says, begins with an appreciation of just how central the state’s backing of public higher education remains. “It’s an extraordinary process,” he says. “These are state institutions. We are on state grounds; all the buildings are state supported and state built.” Such funding for Eastern’s physical footprint — those structures where teaching, research, campus living and administration take place — are part of the so-called capital budget, Buri explains.

Such appropriations, along with the tens of millions of dollars allocated to maintain campus buildings and infrastructure, have been key in ensuring that EWU and its students will continue to be a “driving force” for innovation and economic development in Washington.

Over the past decade, Eastern has seen a string of successes in this area. Among the more notable projects: the aforementioned $67 million for the Interdisciplinary Science Center, $45 million for its ongoing Science Building renovations (with a projected $58 million more to come) and $65 million for Patterson Hall’s high-tech makeover in 2014. Such appropriations, along with the tens of millions of dollars allocated to maintain these and other campus buildings and infrastructure, have been key in ensuring that EWU and its students will continue to be a “driving force” for innovation and economic development in Washington.

Equally, if not more important, however, is the other side of the state support coin: funds appropriated as part of the “operations” budget. These include salaries for faculty and staff, purchased goods and services (things like maintenance gear and laboratory equipment) and, perhaps most critical for EWU, student financial aid and support.

“Financial aid is certainly among the important things that are dealt with on that side,” says Buri. “Fortunately, Washington state has one of the most benefit-rich financial aid systems; it’s the envy of many others states, and hugely helpful to our students. This is true especially for the students we serve, our first-generation students and our Pell [grant] eligible students.”

The state typically ends up covering about 50 percent of operational expenses. Most of the rest comes from students in the form of tuition and fees. Here, too, the state plays a key role: Washington law allows its legislature to determine roughly how much state-supported colleges and universities can charge.

Concerns surrounding the cost of higher education have long guaranteed that tuition, whenever it comes up, is going be a hot topic. During the last major round of tuition- and fee-setting eight years ago, Buri recalls, he and Rodolfo Arévalo, Eastern’s president at the time, worked the Capitol Building hard. Our students should not be expected to cover a greater percentage of operating expenses, they argued, because the financial challenges faced by much of EWU’s student body are more acute than perhaps any other institution in the state. “It was, basically, ‘Ok, how do we make sure this makes sense for our students?’” Buri says. Their arm-twisting had the desired effect, and Eastern remains Washington’s best value in higher education.

Making sense for students, of course, doesn’t just involve keeping Eastern affordable for the current students. It also means opening the door for future Eagles. On this score, during the previous legislative session Buri worked with Eastern’s former interim president, David May, as part of a broad coalition of advocates working to boost access for students from across the region. Successes included new laws that provided funds to help prospective students complete financial aid forms; support for community partnerships aimed at encouraging post-secondary education; new grants and low-cost loans for those with financial needs; and expanded access to programs, like Eastern’s popular Running Start, that allow students to earn college credits while still in high school.

Two additional big wins came with legislative support for EWU’s new bachelor’s degree program in nursing, and funding to support an expansion of its offerings in cybersecurity studies. Long home to a successful (and popular) pre-nursing program, university officials had for years recognized that the obvious next step was a four-year program. In cybersecurity, EWU’s Stu Steiner, an assistant professor of computer science, has been carving out a niche for Eastern in this increasingly in-demand field.

“During the last session, we wanted to be especially thoughtful about workforce needs,” Buri says. “We saw, for instance, that there was a great shortage of nurses, but we just didn’t have the funding to say ‘Hey, let’s expand the nursing program.’ So we had to go to the legislature. The same for cybersecurity. I was able to go to Dean Bowman and Stu Steiner and ask, ‘Are we turning away qualified students?’ Their answer was, ‘Yes, yes we are.’”

From there it didn’t take much convincing to help lawmakers recognize that funding Eastern’s growth in these areas was a win-win for both EWU and the state. This is not to suggest it’s always so uncomplicated. Not every good idea moves forward, and not every critical need gets funded. Having served himself, Buri is more than a little sympathetic to the push and pull that characterizes life for an elected official.

“It’s hard,” he says. “A very difficult job. I remember when I first got to EWU somebody came up to me and said, ‘Why aren’t they funding higher education better?’ And I said, ‘Well, higher education is a priority for almost everybody, but not necessarily among their top five priorities.’ Sometimes in higher education — and I think we all have this tendency — we only talk to people who think like us. We think: ‘Higher education is the most important thing to me. How can it not be the most important thing for you?’ For legislators, it sometimes comes down to really tough choices: ‘Well, do we put additional dollars in higher education, or do we limit how many kids qualify for health care?’”

There are certain things that are in the state constitution that you have to do, Buri adds, such as funding K-12 education at a mandated level. “One thing you hear a lot: the state ‘educates, incarcerates and medicates.’ And the ‘incarcerate and medicate’ parts are also mandated. So by the time you get down to the portion of the budget that’s discretionary, it’s smaller. Higher education fits in that bucket, as do social services. So it’s a tug of war, in a way. A challenge.”

Buri grew up in Colfax, a picturesque town of 3,000 located on State Highway 195, about 18 miles northeast of Pullman. Situated in the heart of one of the world’s most productive wheat-growing regions, pretty much everybody in Colfax is connected to agriculture. Buri’s family is no exception. His relations have cultivated wheat in the area’s rich Palouse soils going all the way back to the 1880s.

As a young person, Buri resisted the pull of nearby Washington State University and instead chose to attend a small college in Arizona. “I thought I needed a little distance from mom and dad,” he says with a laugh. After college he settled in Northern California, just across the bay from San Francisco. But rural Washington remained close to his heart. “I was in Marin County for a few years — it was great living there, such a beautiful place. But I really wanted to get back home. I loved Palouse country; just really loved the people of Eastern Washington.”

So back to Colfax he came. At first, in the early 1990s, Buri worked as a banker. But it wasn’t long before the lure of public service drew him in. He first began serving on the local Chamber of Commerce, eventually becoming its president. Next, with his two eldest children attending public schools, he turned his attention to education policy, winning election to a seat on the school board.

Colfax may have been small, but, as the county seat of an important center of agriculture, it attracted the attention of both sitting and prospective state and federal lawmakers. Buri quickly discovered he enjoyed interacting with the political set.

“It was just amazing to me,” he says. “I was coming from California, where I never met anybody in office — not the school board, nothing. One meeting in particular really stands out to me. Congressman Tom Foley, who happened to be Speaker of the U.S. House at the time, came to a Chamber of Commerce dinner. I was involved in the chamber at the time, and I remember sitting at a table with Foley — in a room with maybe 20, 25 people. I’m thinking, ‘This guy is two heartbeats away from the presidency! And here he is, and we’re sitting here visiting.’”

A short time later, an opportunity arose for Buri to serve as a legislative assistant for Larry Sheahan, who, at the time, served as a Republican state senator representing Legislative District 9. The job involved countless hours driving to face-to-face constituent meetings across the vast district. Buri loved it. A few years later, in 2004, a seat on the House side opened up. Buri threw his hat in the ring and won.

District 9’s boundary pushes right up to the southern border of Cheney, but doesn’t include EWU. The district does, however, encompass Pullman and WSU, so Buri often immersed himself in issues related to higher education, earning, in the process, a seat on the legislature’s Higher Education Committee. As a politician, Buri was something of a rarity: the moderate Republican. But through his work ethic, familiarity with the issues and genial manner, he earned the respect of both those in his own party — he served as the GOP’s minority floor leader after winning reelection to just his second term — and the Democrats who controlled the chamber.

Buri left elected office and headed to Eastern for that most familiar of political motives — focusing more on family. In his case, however, he wasn’t using his near relations as an excuse or euphemism. His wife, herself a former assistant to a Democratic representative, had just given birth. It was time, he felt, to shift priorities.

These days, Buri admits working both sides of the aisle, even on once broadly supported issues like higher education, is tougher.

“I do think that things have changed over time, and it’s an unfortunate change,” he says. “Part of it has always been the natural tension between competing interests I talked about earlier. But a newer phenomenon involves higher education starting to be seen as landing on one side or the other in our culture wars.”

Buri pauses before continuing. “That makes it difficult. I don’t know how else to say it: It makes it difficult. In our region in particular… [another pause, and then a laugh] Ok, let’s just stop at ‘difficult.’ But I really want to emphasize how fortunate we are to have great support from both parties.” Those supporters, he says, include alumni and former university staff members such as Drew Shirk, executive director of legislative affairs for Gov. Jay Inslee, who attended Eastern’s graduate program in public administration, and Alicia Kinne-Clawson ’07, a former ASEWU president who is now the influential coordinator of the state senate’s higher education and workforce development committee. There’s Joe Schmick ’80, R-Colfax, now representing Buri’s old district, who studied accounting and economics at Eastern, and Matt Boehnke ’90, R-Kennewick, an EWU ROTC graduate who majored in government. And this is just the short list, Buri says.

“I do think that things have changed over time, and it’s an unfortunate change,” Buri says. “Part of it has always been the natural tension between competing interests I talked about earlier. But a newer phenomenon involves higher education starting to be seen as landing on one side or the other in our culture wars.”

“Higher education historically has been a nonpartisan issue, and we really work hard to keep it that way,” Buri says. “We’ve got some really good friends in both parties who champion Eastern Washington University. That’s important. We’re a nonpartisan school that serves the entire region. And I can tell you that our current president, Dr. McMahan, really wants to make sure that we are welcoming to any student who comes to Eastern, and she’s going to share that message with the legislature.”

Going forward, Buri says, ensuring that Eastern continues to serve its students and the region remains his top priority. And though a projected softening of state revenues may signal a reluctance to fully fund Eastern’s list of priorities, he’s as bullish as ever about the university’s prospects.

Buri says he’s always psyched before getting down to business in Olympia, but this year he’s especially excited. It’s the first truly face-to-face meeting of the legislature since the pandemic began, and for Buri, that signals “game on.”

“So last year I was over there, but we didn’t have open, in-person hearings, legislative visits and that sort of thing. But this year there is every expectation that we’ll be doing them again. And that’s essential. A lot of the work is done in formal meetings, but a lot depends on the informal stuff, walking between committee hearings and chatting with members. Saying, ‘Hey, we’ve got this bill — we know you’re supportive, are you hearing about anybody with questions? Other members we should be talking to?’”

In other words, working the halls to influence the influencers. “I always get excited,” says Buri. “There’s just so much energy, and with Covid being wrapped up — or at least in a new phase — I think this session is going to be really exciting, and really productive for Eastern.”