The Road Less Lethal

On the Colville Reservation, deadly car crashes have become a tragic fact of life. EWU faculty and students are determined to change that.

By Dave Meany

To drive along one stretch of the Coulee Corridor, a national scenic byway, is to experience North Central Washington in all its glory. The majestic Columbia River is never far away. Mountains stack up in layers against a distant horizon. At every turn, motorists are greeted by endless acres of stunning landscape sprawling in every direction: sagebrush and native grasses bowing low before the wind, jagged rock formations shooting up to expansive blue skies, green pines and firs holding fast to golden hills.

But this striking landscape creates somewhat of a deceptive beauty, one that masks a terrible reality of navigating this breathtaking expanse of State Route 155 on the Colville Reservation. The two-lane highway has long been among the state’s most deadly; few who have grown up navigating this treacherous path are free of the weight of its tragic memories.

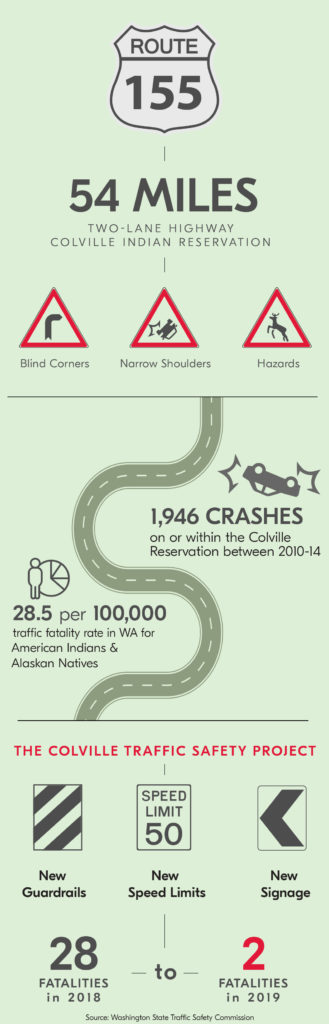

Like many other reservations nationwide, the remote roads crisscrossing the Colville Tribe’s land are fraught with hazards: blind corners, narrow shoulders and dangerous passages. Not surprisingly, traffic fatality rates on these roads, as compared to other state highways, are high. Over the years, too many wooden crosses have become fixtures along these routes, too many lonely memorials built to commemorate a friend or loved one lost.

“We are almost five times more likely to die in a car fatality than the national average,” says Adam Amundson ’16, a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes.

Having grown up in Omak and Nespelem, Amundson knows the lay of the land as well as anyone. Yet he was almost one of those statistics.

In 1996, a tired Amundson had just completed a 16-hour shift at Colville Indian Precision Pine, a since-shuttered sawmill operated by the tribe. He hopped in the passenger seat of his Chevy Chevelle as a friend drove them home on a county road near Okanogan. They didn’t make it. Amundson doesn’t recall many details of the one-vehicle crash, only that he woke up after two weeks in a coma unable to walk, talk or think straight. It would take him six months to relearn to walk on his own.

Amundson says crashes like his seemed like an everyday occurrence on the reservation. But his own near-death experience left him with a determination to change that narrative.

“When you have a fatality within a tribal community, they are so small there is a ripple effect,” says Amundson. “It has an impact on the whole community. If there is any way I can reduce fatalities it is worthwhile.”

That path for Amundson led to Eastern in 2015, where he majored in urban and regional planning after earning an associate’s degree at Wenatchee Valley College. He quickly immersed himself in the department’s many programs and initiatives aimed at assisting tribes on transportation issues, with a specific eye toward exploring Route 155 safety issues on the reservation.

“We’ve had so much tragedy and heartache in Indian Country, that we don’t necessarily specifically identify traffic safety as something we can do something about,” says Margo Hill, assistant professor of urban and regional planning at EWU.

How much tragedy? The Washington State Traffic Safety Commission says 257 American Indians and Alaskan Natives, abbreviated as AIAN, died in traffic crashes from 2008-2017 on reservation roads. This put the AIAN traffic fatality rate at 28.5 per 100,000 people — the highest rate in the state for any ethnicity. According to the safety commission, there were 1,946 crashes on or within five miles of the Colville Reservation between 2010 – 2014; of those 34 were fatal. Seventy more were reported as resulting in serious injuries.

Sadly, there have been times the tribe has experienced more than 20 fatalities on its roadways in just one year. With only 9,500 enrolled tribal members, such numbers are particularly devastating.

Hill knew EWU could help address these traffic issues by having expert faculty guide students through hands-on service-learning projects. As a Spokane tribal member and Colville descendent, Hill has longtime connections to area tribes and a deep understanding of the challenges they face. Her success in securing grants to fund some of these initiatives only boosted those efforts.

Working within the culture of telling stories to educate tribal members, Hill knew that telling this particular story would require more data. But there was one lingering roadblock. As sovereign nations, American Indian reservations are not required to submit vehicle crash data. Only in the last decade has that data been available, and it’s been sparse at best.

Thus, began a collaborative, and successful, project between Eastern, the Colville Tribe and the state traffic safety commission to drastically reduce vehicle fatalities on reservation roadways.

“The tribe was determined to reduce fatalities,” says Hill. “They were eager to work with the traffic safety commission and EWU to identify problems and create a culture of traffic safety.”

It’s been a long road, to say the least. Transportation planning and engineering can be a bureaucratic maze in any community. Reservations nationwide include a mix of tribal, local and state government interests — along with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs — all of which create jurisdictional complexities with law enforcement, emergency medical services, crash reporting, road maintenance and capital safety projects.

Thanks to a grant from the traffic safety commission, the Colville Tribe was able to navigate these complexities by hiring a traffic safety coordinator to track crash and fatality data — something not done before. The coordinator worked with a team of students and staff from EWU, traveling to each district on the reservation to conduct surveys, workshops, and focus groups with tribal members and leaders.

Their research also identified attitudes on seat belt usage, drinking while driving, poly-drug-use, and distracted driving (mostly texting) within the reservation boundaries.

The Colville Traffic Safety Project, which included EWU graduate students earning their Executive Tribal Planning Certificate, produced remarkable results for the Colville Confederated Tribes – authorities say traffic fatalities dropped from 28 in 2018, to only two in 2019.

“My eyes welled up because it felt good to know that families weren’t losing loved ones on the road,” says Kylee Jones ‘18, who worked on the safety plan as part of her senior capstone. “We literally do work that helps save lives here at EWU,” adds Hill.

The drastic reduction in fatalities happened because multiple layers of agencies, along with eager students, committed themselves to making a difference.

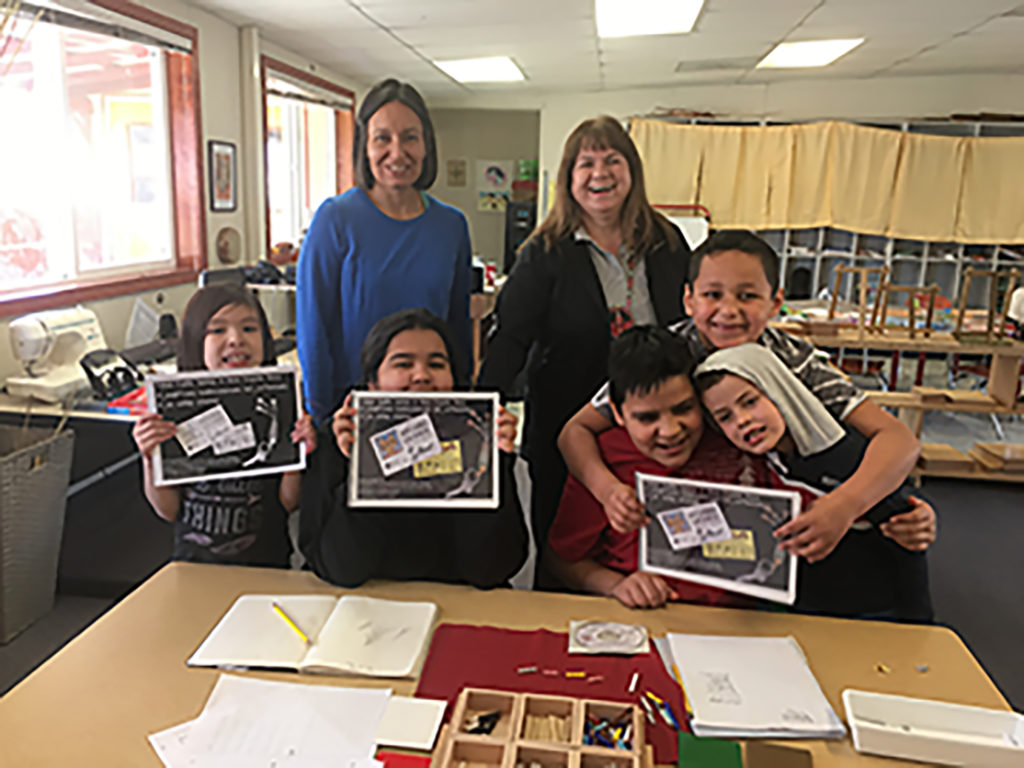

Hill says the EWU team, for instance, spent a week in Inchelium conducting workshops to educate youth on traffic safety. “The youth identified issues they thought were contributing to vehicle crashes and fatalities such as drinking and driving,” says Hill. “EWU students conducted a scripting workshop with the teenagers, a key demographic for this project, who ended up producing a series of public service announcements incorporating interviews with first responders.”

All the information gathered, including GPS data collected at crash sites by the traffic safety coordinator, assisted the Colville Tribe’s Department of Transportation in implementing proven safety measures — such as obtaining additional guardrails in strategic locations along roads like SR21 and SR155.

The project also produced a unique, illustrated storybook, Tribal Traffic Safety: A New Coyote Story. Written in English, EWU worked with tribal language elder, Elaine Emerson, to translate the story into dialect and record it. The books were delivered to the Colville Tribal School, where they will be used to communicate important messages such as: “Wear your seat belt,” “Don’t speed,” and “Don’t text and drive.”

“My goal in transportation planning is to help those who are disproportionately and adversely impacted by transportation,” says Jones. “Planners don’t always see the fruits of their study recommendation and project outcomes, so I am incredibly grateful to know that our contributions have helped save lives.”

While earning his bachelor’s degree at Eastern, Amundson completed his own SR155 research that would provide critical assistance to the tribe’s Traffic Safety Project. He uncovered fatal accidents that were never properly recorded with the state. And he came up with some low-cost solutions such as simple alignment signs (chevrons) to warn drivers of upcoming turns, dangerous curves or other hazards.

Amundson was mentored by Dick Winchell, a professor emeritus at Eastern who is an expert in tribal planning and transportation issues. Winchell, along with Richard Rolland, previous director of the university’s former Northwest Tribal Technical Assistance Program, is credited with starting the whole concept of tribal planning programs at Eastern.

Another alumna mentored by Winchell, Angelena Campobasso ’10, ’12, is an enrolled member of the Colville Confederated Tribes and grew up on the reservation. As program manager for EWU’s Small Urban Rural Tribal Center of Mobility, or SURTCOM — a byproduct of Winchell and Rolland’s earlier work — she too shares a passion for improving the welfare of those living in Indian Country.

Campobasso spent time as the Colville Tribe’s Senior Transportation Planner, where she helped bridge all the stakeholders involved to commit to the traffic safety project.

“For the first time in years, the [Colville Tribe] was able to create crash data. How many crashes, types of crashes and on what roads,” says Campobasso. “The crashes were mainly focused on the state highways. This way we could show the Washington State Department of Transportation exactly where the problem areas were within the reservation.”

Identifying those problems led to the solutions, like adding the new guardrails as well as paving highways with adequate stripping, improving crosswalks with lighting in school zones, and placing signage in strategic locations.

“We had no traffic fatalities that involved our youth or a young adult [in 2019]; no one under the age of 65 passed away on our roads this year from alcohol, drug-use, distracted driving, speeding, weather conditions, animal crossing, none! This is the first time in years!” said Hill, who managed the Eastern team’s role in this project, noting how the university’s training is so critical to providing tribes with technical support.

While at EWU, both Amundson and Campobasso were awarded Eisenhower Transportation Fellowships, an honor for students pursing degrees in transportation-related disciplines (Campobasso earned the distinction twice). They both traveled to Washington, D.C., to present their research to experts from around the world at the annual meeting of the Transportation Research Board — a division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

These accomplishments were just one reason these two EWU graduates were equipped to help ensure their beloved tribe wouldn’t have to experience so much heartache along Route 155. Campobasso knows plenty of people who have lost loved ones. In addition to his personal near-death experience, Amundson’s heartache only deepened in 2013, when his 22-year-old daughter died in a car crash. While the accident was not on tribal land, he was even more motivated to see traffic safety improvements. And now he gets to do it every day as a planning technician for the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, focusing on economic development, transportation planning and land use.

Everyone involved in the traffic safety project would like to see continued advances in tracking crash data, which in turn could help secure funding for future safety upgrades and roadway improvements that will save more lives.

“There is still significant work to do and thousands of miles of unsafe roads on tribal lands,” notes Kylee Jones, who is now with the Spokane Regional Transportation Council.

For Margo Hill, this project typifies the partnerships that make Eastern so valuable to the communities it serves. It’s the type of story she wants elders to pass on to the next generation who live on tribal lands.

“My work at EWU is not just an academic exercise,” says Hill. “I want to do work that is meaningful to our tribal communities. If I can support tribal students while they are here at the university — help them find solutions for their tribal communities — then I’ve done my job.”