By Melodie Little

In the early 20th Century, just a few years after Homer Plessy was denied access to “White Only” streetcars in New Orleans, a new form of racial exclusion began to take hold across the nation, one that would become, in its way, a defining pillar of America’s segregationist past.

Racially restrictive real estate covenants — language forbidding the sale, transfer or use of a property to non-white buyers or renters — are today mostly forgotten. But during the early and middle years of the previous century, such covenants were used to enforce a segregationist status quo that pushed families of color, many of them fleeing Southern racial violence, into overcrowded, substandard housing throughout the North, Midwest and West.

The immediate effect of these covenants (and related restrictions) was to create a separate, unequal American housing landscape. Their legacy has been to deny millions of Americans a fair shot at gainful home ownership, a crucial avenue toward building multigenerational wealth and housing stability.

Enforcement of racial covenants was ended by the Supreme Court in 1948, and all forms of racial restrictions on property were made illegal by the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968. But, surprisingly, the onerous language of these legal barriers remains alive to this day, buried deep in the wording of deeds, plat maps and the property titles of unsuspecting homeowners — both across the nation and right here in Eastern Washington.

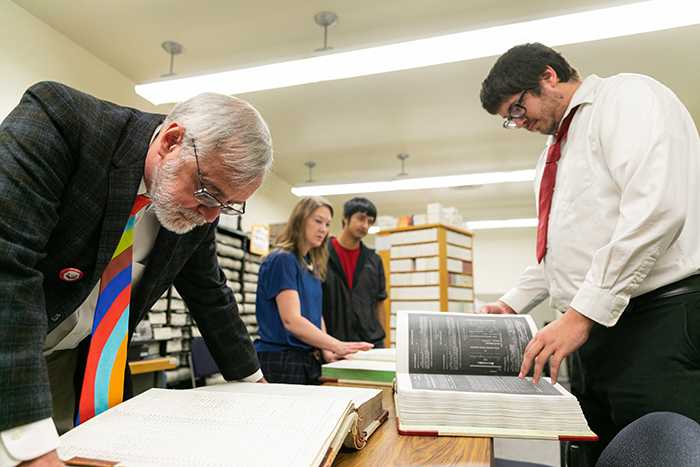

It’s a chilly Friday morning in October, and a small but determined team of researchers with EWU’s Racial Restrictive Covenants Project are ready to hit the road. Today’s trip will take them from their rendezvous point in Spokane some 160 miles west to Ellensburg, Washington. There they will spend a long day examining property records at the Central Regional Branch of the Washington State Archives.

Once on site, the team — including student workers and volunteers — set up their gear and prepare themselves to navigate a sea of records. Though many of their sources are decidedly analog — covenants located in decades-old bound volumes of records are common — much of the team’s analytical work is done in the digital realm.

Optical character recognition (OCR) programs, for example, are a critical part of the process, allowing the researchers to scan hundreds of property records looking for key words, such as “white” and “Caucasian,” that typically accompany racially restrictive covenants. When they get a hit, the team flags the document for further review.

“It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, except in this case it’s like finding a hundred needles in 10,000 haystacks,” says Tara Kelly, a sociocultural anthropologist who is the project’s director of research. Kelly is leading archival activities alongside project head Larry Cebula ’91, an EWU professor of history who himself has long experience in archival research.

For the past several months, Kelly, Cebula and the rest of the EWU team have been focused on unearthing racial covenants in 20 counties east of the Cascade Mountains. Their work, part of a state-mandated and funded effort, is being done in partnership with the University of Washington, which is handling the research on the state’s west side.

The current project was preceded by the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project at the University of Washington. That project’s initial 2005 investigation focused on racially restrictive covenants and other tools of segregation in Seattle and its suburbs. It was a groundbreaking effort, the first of its kind in a major metropolitan area.

Covenants’ legacy has been to deny millions of Americans a fair shot at gainful home ownership, a crucial avenue toward building multigenerational wealth and housing stability.

A direct result of the project’s eye-opening findings — and the media attention they generated — was that the Washington State Legislature passed two new laws intended to bring added attention to restrictive covenants, and outlined ways to help concerned homeowners remove them.

Despite these initial successes, funding to expand the work was in short supply. Passage of SHB 1335 changed that. For the first time, the state has “allocated funds and authorized teams” at UW and EWU to “review existing recorded covenants and deed restrictions to identify those recorded documents that include racial or other restrictions on property ownership.” When the university researchers discover properties “subject to such racial and other unlawful restrictions,” the legislation adds, the teams will notify property owners and county auditors so that action can be taken to modify or expunge them.

Although it can be hard to grasp how these remnants of segregation had gone largely unnoticed for 70-plus years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled them unactionable, Cebula has a theory: “The vast majority of people have no idea that there is a racist covenant on their property. Have you ever looked at your plat map? Most people never have,” he says. Cebula hopes that will be changing.

At the core of Eastern’s project team are a cadre of dedicated covenant sleuths. Senior staff member Logan Camporeale, ’15, ’17, is an historic preservation specialist with the city of Spokane’s Historic Preservation Office. Camporeale was the first archival researcher to identify racist covenants on the east side of the state and, since 2016, has been a driving force in working with the legislature to help get the project off of the ground. Nicholas Boren, a professional IT specialist, has also been hired to support the project, and student workers are a critical part of the effort. Spokane native Colton Schons, a freshman history major at the University of Washington, is a bridge between the EWU group and the researchers at the UW, while Zachary Welsh, an EWU history major in his senior year, is a key student researcher for the local team. Rachael Low, also an EWU senior, has just joined up as a research assistant.

Thus far, EWU’s project researchers and their student helpers have reviewed full deed collections for Adams, Asotin, Ferry, Lincoln, Pend Oreille and Whitman counties, with two additional counties nearly completed. Their online research of property documents has uncovered some 76 plat maps (covering neighborhoods with 10-100 lots) with racially restrictive covenants applying to about 4,290 houses. An additional 506 restrictive covenants have been discovered in their analysis of deeds and other documents. Several counties were free of racial covenants in their plat maps or deed records; they included Garfield, Okanogan, Pend Oreille and Columbia.

Tracking down covenants in so many different areas has required ingenuity and persistence. Many of the smaller towns lack digital records. In those cases, the team piles into cars and vans and drives out to courthouses and archives, where they often end up wrestling heavy, awkwardly-sized deed books from high storage shelves down onto counters for scanning and review.

Flagging digital files has helped Schons determine that an entire Washington town, Airway Heights, was covered by a single plat map from 1946 that imposed restrictions in the following language: “No persons of any race other than the white race shall use or occupy any building upon these premises, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with owner or tenant.” Cebula says it’s unlikely any of the current residents were aware of the racist plat maps, so the team opted to give the town’s mayor advanced notice before making their discovery public.

Elsewhere in Spokane County, meanwhile, EWU’s researchers determined that barriers to inclusion were also common. Spokane’s use of restrictive property covenants began in the early 1920s, mostly via legal language enforcing the segregation of cemeteries. In the 1940s, discriminatory language began appearing, in both overt and more subtly worded forms, in real estate documents restricting access to both single homes and entire neighborhoods.

In many cases, however, Camporeale says the syntax of exclusion was less than obvious. He recalls, for example, in his earlier research happening upon an advertisement for a 3-bedroom ranch home that boasted its location in a “highly restricted neighborhood” — typically code for “whites only.”

“In Spokane, it seemed like people needed to keep their segregation a little more behind the veil,” Camporeale says.

The densest concentrations of restrictive covenants, the researchers say, mostly surfaced in neighborhoods such as Comstock, on Spokane’s South Hill, along with scattered developments in northwestern Spokane and parts of Spokane Valley.

Camporeale says the phrasing of restrictive covenants was often a form of bigoted boilerplate that was shared among local developers who were platting new neighborhoods. Language such as this example, from a property covenant in Spokane, was common: “No person other than the white or Caucasian race shall own, use or occupy any building or lot in said addition; except this document shall not apply to domestic servants of a different race except in the employ of an owner or tenant.”

The team originally estimated that properties in about 50 subdivisions in Spokane County might contain such language, he said. Turns out the actual number was double that, closer to 100.

In many cases, however, Camporeale says the syntax of exclusion was less than obvious. He recalls, for example, in his earlier research happening upon an advertisement for a 3-bedroom ranch home that boasted its location in a “highly restricted neighborhood” — typically code for “whites only.”

“In Spokane, it seemed like people needed to keep their segregation a little more behind the veil,” Camporeale says.

For his part, Welsh says he was stunned when he first happened upon racist phrases such as, “No race except members of the white race shall live here,” and words like “exclusive,” “blood” and “colored” buried in digital records.

“I didn’t think these things existed. I had absolutely no idea,” says Welsh, who plans to pursue a career in archival research after graduating. This project work, he adds, has been a meaningful addition to his résumé, one that will carry weight in his field.

Team members say there has been a lot of learning as they go. For instance, the OCR sometimes flags a “false positive,” Welsh explains. One time, the flagged word “white” referenced a white heifer in Chelan County that was part of the payment for the property. White and Black were also falsely flagged when the terms were found in people’s last names. In another document, “red” popped up as a flagged word. Upon further inspection, the researchers found it described the color of train cars being sold by a railroad.

In fact, finding covenants is anything but predictable. While a given developer may have added racist restrictions for one development, they might have skipped it when building another.

“These were not just standard operating procedures. Most documented records don’t have it,” says Cebula. A lack of restrictive covenants doesn’t necessarily mean communities were welcoming to all races, he adds: Abhorrent treatment by neighbors was a depressingly common extralegal tactic for excluding people of color.

Although Washington wasn’t the first state to identify restrictive covenants, Camporeale says it is the first state to take broad action to remedy it — including committing $250,000 in funding to each university to cover the cost of student staffing, travel to physically review documents and other project-related expenses. The work was initially estimated to take two years. There’s an understanding now, however, that it will likely take longer.

The American Land Title Association has long been a key driver in removing racist covenants from property documents. Over the years the association has energetically lobbied lawmakers in Washington state, urging them to help remedy a wrong that was, ironically, championed within its own industry.

“It’s bad for business these days,” Cebula says. “It is a historical wrong that they sincerely want to right.”

Of course the legwork required to remove restrictive covenants will not be completed by a lobbyist. Typically, the onus for discovering and remedying anomalies and irregularities in deeds, titles and plats falls to already overworked auditors in county recorder offices. Because EWU and UW are now taking the lead in doing the discovery work, auditors can support rooting out restrictive covenants without scrambling to find the staff hours and funds to cover the effort. For this the state of Washington is to be commended, says Kelly. In nearby California, she says, the state legislature recently passed a law that requires county recorders to do the work.

More recently, Cebula engaged his online students this fall in a digital history project looking into the back stories behind the covenants. [You can read about their findings on the website and smartphone app of the Spokane Historical Society.] Such back stories are something the team isn’t charged with doing and generally lack the time to research. As historians, however, they are very much interested in learning more about the “hows” and “whys” of restrictive policies.

“Questions arise in front of us as we flip through these books,” Kelly says. “We want to know, ‘What prompted these racially restrictive covenants to appear in some cities and counties and not others?’ Or, ‘Why in a county otherwise devoid of racial covenants do we find just one? Why here?’ and ‘Why at this location,’”

The team recently presented their work at the Pacific Northwest History Conference, in Kennewick, Washington. Their session, “Identifying Racist Property Covenants in Washington State: A Progress Report,” brought the community of Northwest historians up to date on the project.

Audience engagement was lively. “I think everyone in the room had a question — some asked more than one,” says Kelly.

“In my decades in this profession, I have never fielded so many questions from the audience,” adds Cebula.

Though he admits there is much work yet to be done, Cebula says he couldn’t be prouder of his team, crediting them with pioneering archival research methods that will likely be adopted by other states and communities that are working to expunge offensive covenants of their own.

Their research findings will also have the potential for published papers and, perhaps, a book or two.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Cebula says he occasionally encounters people who accuse the team of “erasing history” by removing covenants. He says he is emphatic in his response. “I tell them we are not erasing history, we are making history.”

Want to help? The University of Washington has made a call for volunteers to participate in a crowd sourcing project to review digital property records flagged as potentiality discriminatory. Learn more: Racial Covenants Project